Is Your Digester Smaller Than You Think?

By Peter Quosai, MASc Bioprocess Analyst, Azura Associates

The most expensive part of an anaerobic digester is often the corrosion-resistant tanks required to hold massive volumes of digestate at a constant temperature.

Measuring and preserving digester volume is one of the most valuable methods for digester optimization, as it determines the amount of feed that can be fed to a digester and, therefore, the amount of biogas that can be produced.

There are three ways that digesters often lose working volume and three ways to determine if your working volume has been lost.

Working Volume: The True Capacity of a Digester

The working volume of a digester is the liquid-filled space where microbes can glide through and convert organic matter to methane.

While design values are based on total tank dimensions, real working volume changes over time as:

1. Grit (sand, silt, bone, shells, plastics, and heavy inert materials) accumulates at the bottom,

2. Floating crust or foam layers (fibrous mats, fats, and buoyant plastics) build up at the surface, and/or

3. Poor mixing causes dead zones and “short circuiting”, where microbes are trapped in one part of the tank instead of reaching all of the organics, preventing much of it from becoming gas.

A reduction in working volume effectively shortens the hydraulic retention time (HRT) and increases the organic loading rate (OLR), stressing microbial communities and limiting digestion performance.

• Example: A tank designed for 20 days HRT may only achieve 15–17 days if 15–25% of its capacity is lost to grit or crust.

Strategies for Maintaining Optimal Conditions

• Routine monitoring: of OLR and gas yields to identify unexplained losses in performance.

• Crude stick test methods: In some cases, the level of grit in a tank can be estimated by lowering a long pole down a maintenance hatch – use appropriate PPE as there will be biogas and hydrogen sulfide present – to see if the bottom of the digester is filled with material. The same crude methods can be used for a crust layer.

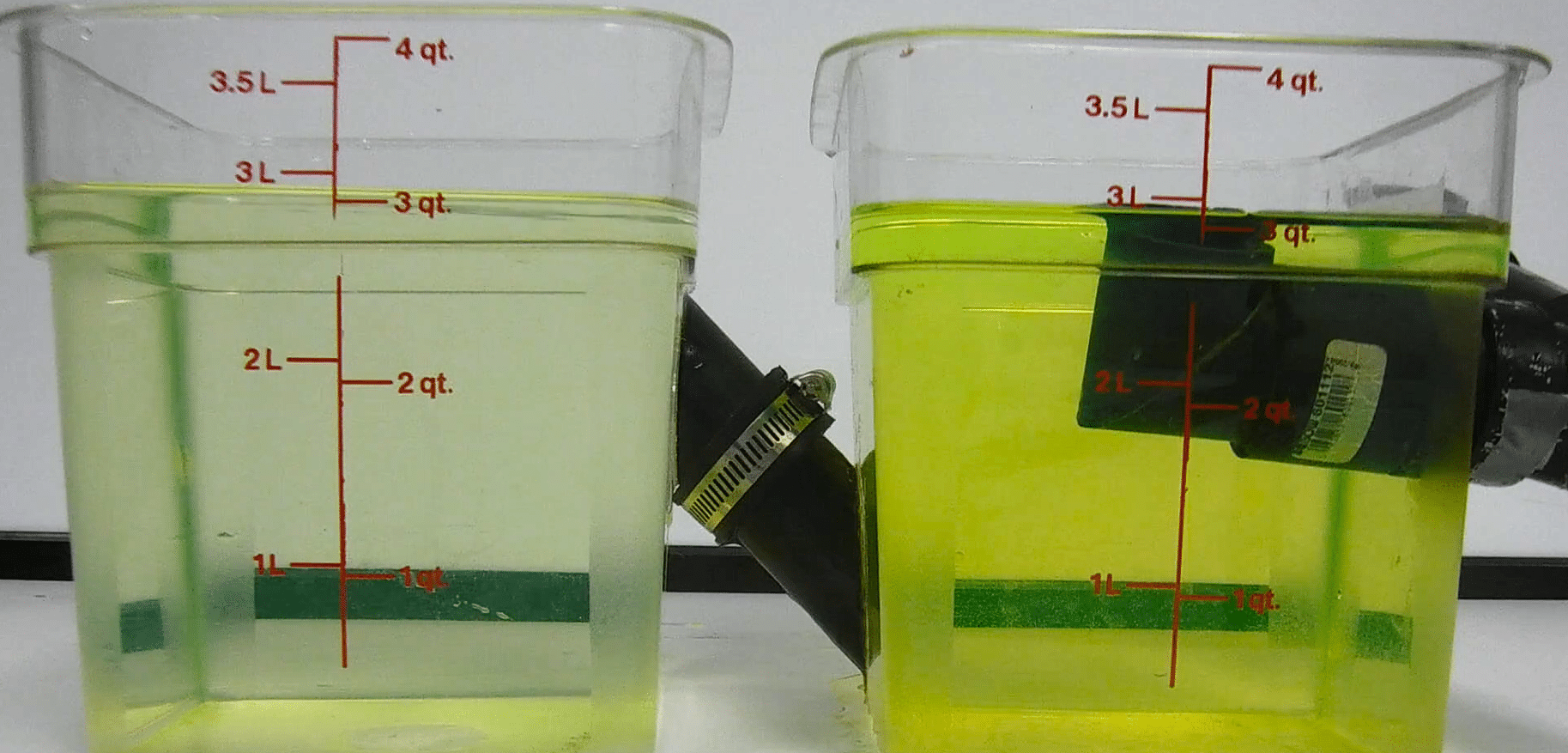

• Tracer studies: A tracer study can be performed by adding a spike of a detectable, soluble, and inert chemical to the digester and recording how the concentration changes in the outlet over time. The speed at which the concentration changes can be used to calculate the working volume. Tracer studies are the only way to accurately determine if short-circuiting is preventing a digester from achieving nameplate capacity.

Anaerobic digesters are dynamic systems where biological performance is inseparable from physical constraints. True optimization requires not only feeding and mixing strategies, but also preservation of working volume through periodic estimates of working volume and controlling grit, crust, foam, and mixing.

By maintaining stable HRT and OLR, operators can safeguard microbial activity, extend asset lifespan, and maximize renewable energy production.

For more information, read our Efficiency Magazine.

Comments